Tables, Trees, and Triples

Original Author: Nic Weber

Editing & Updates: Bree Norlander

Introduction

Susan Leigh Star once famously wrote that “Information science is the study of boring things.” (Star, 2002) PDF. She meant this in loving way. As a field of practitioners and researchers we’re concerned with the organization and encoding of information, as well as the standards and practices that govern reliable knowledge production. This requires us to study and become versant in particular “boring” details of how information is represented within broader information systems and infrastructures. An information infrastructure is, by Starr’s account, highly relational. Information and infrastructures mean different things to different people at different points in time. Data is no different. In fact, there is a soundbite that you may come across in the data curation community that goes like this:

One person’s metadata is another person’s data.

(Here’s a humorous example.) This quote is getting at exactly what Star meant by the relational nature of information and infrastructure. That is, all data are contextual - they mean different things to different people at different points in time. The definition of data that we use in DC I and II recognizes this through the idea of types and roles: Data are types of information objects playing the role of evidence. The role of evidence will be contextually dependent upon who is using what data, when, and for what purpose. (As we begin to engage with topics for DC II it’s important to keep this idea of the relational nature of data and infrastructures in the back of our minds. Many of the decisions you’ll face in practically doing data curation don’t have a right or a wrong answer. They have certain approaches which are more valuable or useful given a certain context. As we come to the conclusion of the quarter I’ll try to re-emphasize places where readings, discussions, and lectures have provided helpful ways to toggle back and forth from the immediate “boring” details of data curation, and the broader conceptual settings where these “boring things” become salient.)

Given the fundamental relational nature of data we should start the course off by thinking about how to make decisions about ways data should be represented and made accessible to users. Because, if we accept that choices we make in how to structure, represent, and format data in turn shape access and use, then there must be some guiding principles, or at least an explanation that helps us make sense of these different choices. Indeed, there are a many different paradigmatic ways to approach the relational nature of data. [Weber’s] mentor Allen Renear, along with Elizabeth Wickett and Andrea Thomer, have nicely summarized this data concept as being about the abstractions afforded by using “Tables, Trees, or Triples.” This first module unpacks some of their ideas and helps frame our course.

Levels of abstraction

Let’s begin with an anecdote about a “thing” or an “instance” of a thing that is made into data.

An ecology graduate student sitting in the Brazilian Atlantic rainforest biome observes a species of a frog. Not just any frog, an Adenomera of the genus leptodactylid. She makes a mark of the observation in her field notebook. A while later she observes another Adenomera. She makes a similar mark in her field notebook. But, now she also makes a third mark - observing the pattern dispersion in a 4x4 meter box where the observations occur. She further records some metadata that includes the lattitude and longitude of the observations, as well as the time of her observations. (This is an actual observation you will find described in this paper.)

The data that our intrepid ecology graduate student has collected is made portable by her taking the field notebook back to her lab, and entering the data into a computer. But, she has a decision to make: How should she enter that data in her computer? Should she open an Excel sheet and begin structuring the data into rows and columns? Should she fire up MySQL and create a new database table? Maybe she is in a hurry and simply wants to write up her fieldnotes in a plain text file and go have a beer.

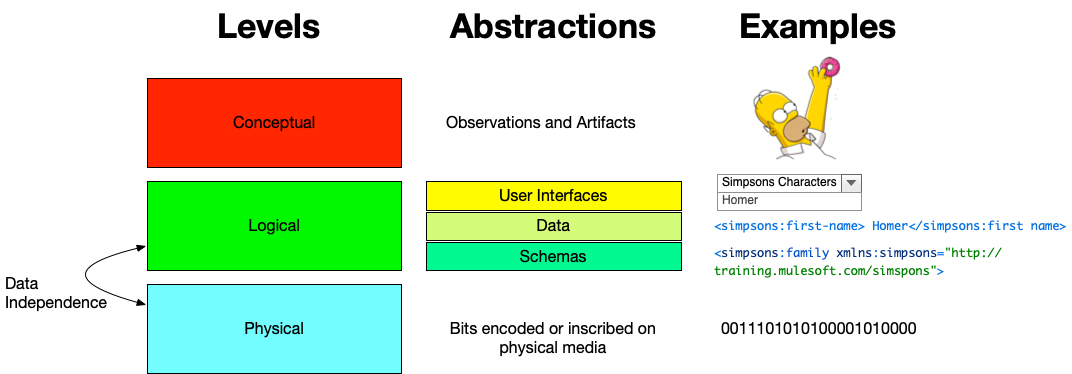

The choices she makes in this brief instance are what transforms her observations from the conceptual level of “a thing that happened in the world” to the logical level of how that data are structured with a standard, or non-standard schema. Our computers further abstract this data into a physical level where the data are encoded or made machine interpretable as files, and bits (1s and 0s) written to a disk and stored on a server or drive somewhere.

These three levels - the conceptual, logical, and physical - are all related to the idea of abstraction. This terminology is common in the domain of database management and refers to, “the process of hiding irrelevant information at each level of a database” (reference). We abstract away from the messiness of the conceptual world by using logic that structures information in physical storage and retrieval hardware. (You can imagine that without abstraction we might contantly be staring at 0s and 1s on our screens instead of charts and GIFs and tweets.)

The choices made at the logical level will have profound consequences for later reuse. And while our ecology graduate student has many choices available to her (will she or will she not go have that beer?) at the logical level of data representation her choices typically break down into three categories: Tables, trees, or triples.

Tables

The idea of a “table” comes from the Edgar Codd’s relational data model (1969) where first-order predicate logic is used to express ordered lists of related instances (tables), as well as relations between tables (the database). A bit of background on Codd’s model: The relational database was born out of necessity. In the late 1960’s as governments and businesses started to move much of their data gathering into a digital (or quasi-digital) form for computers to interact with there were many idiosyncratic ways of doing so. Each different way depended upon the computing environments, and the organizations that were storing data. To a computer scientist this was chaos. And to Edgar Codd there was a simple and elegant solution: Tables. The relational model for database management is a structure and language consistent with first-order predicate logic - it conceives of “tuples” (ordered lists of data) grouped into relations. In short, the relational model is “a declarative method for specifying data and queries: users directly state what information the database contains and what information they want from it, and let the database management system software take care of describing data structures for storing the data and retrieval procedures for answering queries” Wikipedia. In other words, a user should simply structure the data (tuples) in terms of rows and columns, and use a simple logic to declare how those rows and columns relate to one another. How simple: Tables are relations of data and databases are relations of tables. In this way, tables give structure to data through a column (an attribute or variable), a row (an observed instance) and a value (the data represented as a number, text string, category, etc.). The power of the relational approach to structuring data is that we can store large amounts of information without redundancy, and depend on querying syntax to retrieve subsets or “views” of the data. End users don’t need to know anything about data at the physical level, they only need to know enough about the logical representation of the data (some attributes) in order to find what they’re looking for.

Most of the graphical user interfaces (GUIs) that provide access to information in our lives - from mobile apps to library catalogues - are driven by databases that further hide this logical model from end users. We don’t need to know anything about the schema in Zappos’ database to know that if we select brand - converse and color - black and size - 7.5 we can locate our new Chuck Taylor All Stars for summer.

Excel - and before that Lotus 1-2-3 - are undeniably the most interesting mix of a graphical user interface and a database that allows us to easily create tables of information (or spreadsheets) that mirror the relational model of data management. While Excel doesn’t easily facilitate the linking of tables to one another (though it tries to mimic this with worksheets within workbooks), it still gives us the structuring power of the table in terms of columns, rows, and values. And like a database this allows end users to abstract away from the physical level of data storage.

Tables help provide a structure for related observations or instances of a thing. But, tables are not well suited for expressing logical structures that go beyond simple observed instances. Put simply, a database, in being based on a rigid first-order predicate logic, doesn’t handle nuance well.

Trees

A declarative markup language is quite literally built for expressing nuance. Charles Goldfarb in 1981 developed the notion of a descriptive markup language that could, in ways similar to the relational data model, allow for complex information to be expressed at the logical level, but not require that users know anything about physical storage. A markup language, like HTML or XML, structures data in a hierarchical fashion. It depends upon a schema - which defines an element or tag set - and the application of tags to give structure to our data (values).

A markup language can therefore express complex relationships through its schema and structuring of information. And this logic - the hierarchy that will be defined by our schema - in turn allows physical levels of information storage that are, relatively, efficient at retrieving complex information.

Let’s use an example from William Blake’s poem “The Sick Rose” from the anthology Songs of Experience.

Our computers can easily render this JPG, but they cannot easily process or make sense of the data of this poem (stanzas, lines, or words). Putting this type of information into a database also doesn’t make a sense. What would we even call an attribute, or a value of this instance?

Writing an XML schema that defines properties of Blake’s work - like anthology, poem, stanza, and line - will allow us to create a structured data representation of the poem that can be easily be stored and retrieved at the physical level.

<anthology>

<poem>

<heading>The SICK ROSE</heading>

<stanza>

<line>O Rose thou art sick.</line>

<line>The invisible worm,</line>

<line>That flies in the night</line>

<line>In the howling storm:</line>

</stanza>

<stanza>

<line>Has found out thy bed</line>

<line>And his dark secret love</line>

<line>Does thy life destroy.</line>

</stanza>

</poem>

<!-- more poems go here -->

</anthology>

(Before we continue, you might be wondering, “how does that look like a tree?”. Or maybe you’re not wondering, but I [Norlander] did. In fact, the term tree in this case comes from a mathematical definition of a tree, not the definition of that large plant in your yard. For more information, check out this Wikipedia article.)

The XML tree provides for relations between data both through the schema, and through the syntax. An anthology contains a poem, a poem contains stanzas, and stanzas contain lines. Each indentation in the above XML nests these elements further inside one another. This is what creates the “hierarchy” that our computers interpret as a tree.

The tag that closes the poem and contains a note <!-- more poems go here --> is important. This hints at the idea that we can add more poems with more lines to the anthology markup by simply using the pre-defined schema. So, similar to a table we have the ability through logic to relate data to one another, but we also gain the ability to use the syntax and nesting to further refine and express relationships between data that are hierarchical. The ability to express relationships in structured text is what makes a hierarchical form like a tree so valuable for publishing electronic content.

Data Independence

What I’ve been describing in the tables and trees sections thus far - this idea of abstracting away from physical storage to a logical level of data structuring - is the concept of Data Independence.

By organizing data at a logical level, either through relations (e.g. a relational database) or element sets based on a pre-defined schema (e.g. hierarchical models using XML or JSON), we can easily add new data or new relations without having to rewrite our entire database system (or our XML schema). That is, data independence is the ability to present the stored information (at the physical level) in different ways to different users. So we can offload the organization and structure to a general schema, and we can then build rich graphic user interfaces that display the data any way we choose. Data independence also means that we can easily modify and update applications that depend on this structured schema, and minimally impact end-users that interact with a graphic user interface. Both tables and trees make this logical level data independence possible, and allow data to grow (or scale) more or less infinitely.

The following image depicts the relationship between the concepts we’ve been talking about thus far. Note that a separation between the physical level and the logical level is what enables data independence. Here the logical level practically is split again into three areas where, as data curators, we manage different aspects of our user’s experience. At the schema level we define the logical representation and relationship between data, at the data level we manage information, create and edit metadata, and provide documentation, and at the user interface we provide data to end users (in this picture, as a drop down menu).

Trees and Tables

You may have left the last section thinking to yourself, “If the syntax of a markup language affords us so much expressive power, why not use a markup language like XML for all data?”

What we gain in expressive power from a markup language comes at the expense of computational tractability. The more syntax we have to write to define how and where a set of data are interpreted by our computers at the physical level, the more difficult and expensive it will be to retrieve that data.

This tradeoff can be made a bit clearer if we look at the differences between the two most widely used notation systems for hierarchically structured data: JSON (javascript object notation) and XML (extensible markup langauge).

XML, or a hierarchical tree like structure of data, depends on nesting element sets within one another (these were the indentations in our Blake XML). If we want to represent these same elements in a stream - that is in something that our computers can efficiently retrieve as a list or dictionary - JSON is better suited to this task than a markup language. This is, partially, because JSON is based on a programming language not a markup standard. JSON treats an object as independent from any kind of semantic meaning that humans might reliably expect that object to have. JSON, in its syntactical structuring of data, is therefore able to achieve a kind of independence at the data level that XML cannot. But removing this semantic (or contextual) meaning has both affordances and limitations. By keeping data objects “independent” from the schema we have the ability to compute against (that is retrieve, reorder, and analyze) objects efficiently. But, we also lose the ability to embed meaning in the structure of our data. (Note: If you come from a computer science background you may recognize this as the concept of object oriented programming.)

This will make more sense by looking at how the two different notation systems structure the same information. For our example, let’s use Homer Simpson and his relatives (This from a Stack Overflow discussion that has been raging for over 9 years. If you search hard enough you’ll probably be able to find my [Weber’s] own contribution to this debate, but I don’t encourage it).

In JSON we could represent Homer’s familial relations with a list in the following way:

{

"firstName": "Homer",

"lastName": "Simpson",

"relatives": [ "Grandpa", "Marge", "The Boy", "Lisa", "I think that's all of them" ]

}

The same information, when represented in a markup language like XML (which follows a tree-like hierarchical form), looks like this:

<Person>

<FirstName>Homer</FirstName>

<LastName>Simpsons</LastName>

<Relatives>

<Relative>Grandpa</Relative>

<Relative>Marge</Relative>

<Relative>The Boy</Relative>

<Relative>Lisa</Relative>

<Relative>I think that's all of them</Relative>

</Relatives>

</Person>

Practically, we can think about how we would retrieve data from these two representations of the same information, and the efficiency of our computers to do so.

Just looking at the syntax we can see that JSON is more computationally efficient. There are fewer lines of encoded information and fewer assignments of our computer’s memory to represent the same information. In JSON we can represent all of the relatives in a simple list, and then use the order of that list to retrieve any member (e.g. > Relatives[4] returns Lisa).

In the XML we represent each family member with a <Relative> tag. In our XML schema we would have defined what the <Relative> tag means and rules that govern its proper use. If we want to retrieve the fourth relative Lisa from this tree our computers have to read each line until it comes to the fourth <Relative> syntax marker, store the value Lisa in our RAM, and then return it to us. This is undeniably a simple retrieval task that won’t overwhelm any sufficiently powered laptop, but we can imagine this getting much more complex and computationally taxing the more data that we have nested in a markup language like XML. Our computers would have to traverse hundreds or thousands of lines of the XML tree to retrieve data that could be simply listed.

But, the tradeoff is that in JSON we don’t have any semantic meaning built into our syntax. In the first JSON example there is no semantic meaning for a string of characters assigned to a list. So we only know something about that list based on the position of any one data object in relation to the entire list. We could quickly retrieve the fourth object in that list, Lisa, but our computer has no meaning for that object - only that it is fourth in the list of objects. XML can use a schema to define each markup tag and how it should be used. To understand this tradeoff issue at scale, let’s represent a bit more data about the Simpsons family in the two notation systems. (This example comes from MuleSoft XML developers.)

In JSON we could represent family members and their ages as follows:

[

{ "lastName" :"Simpson",

"firstName" :"Homer",

"age" :39

},

{ "lastName" :"Simpson",

"firstName" :"Lisa",

"age" :8

},

{ "lastName" :"Simpson",

"firstName" :"Bart",

"age" :10

},

{ "lastName" :"Simpson",

"firstName" :"Marge",

"age" :36

},

{ "lastName" :"Simpson",

"firstName" :"Maggie",

"age" :1

}

]

In XML, the representation of this information looks like this:

<?xml version='1.0' encoding='ISO-8859-1'?>

<simpsons:family xmlns:simpsons="http://training.mulesoft.com/simpsons"">

<simpsons:member>

<simpsons:last-name>Simpson</simpsons:last-name>

<simpsons:first-name>Homer</simpsons:first-name>

<simpsons:age>39</simpsons:age>

</simpsons:member>

<simpsons:member>

<simpsons:last-name>Simpson</simpsons:last-name>

<simpsons:first-name>Lisa</simpsons:first-name>

<simpsons:age>8</simpsons:age>

</simpsons:member>

<simpsons:member>

<simpsons:last-name>Simpson</simpsons:last-name>

<simpsons:first-name>Bart</simpsons:first-name>

<simpsons:age>10</simpsons:age>

</simpsons:member>

<simpsons:member>

<simpsons:last-name>Simpson</simpsons:last-name>

<simpsons:first-name>Marge</simpsons:first-name>

<simpsons:age>36</simpsons:age>

</simpsons:member>

<simpsons:member>

<simpsons:last-name>Simpson</simpsons:last-name>

<simpsons:first-name>Maggie</simpsons:first-name>

<simpsons:age>1</simpsons:age>

</simpsons:member>

</simpsons:family>

Again, just looking the two approaches structuring data we can see that JSON is more efficient - there are fewer lines and the data has independence. For example, we could also easily rearrange the data in JSON to simply be two lists:

[

{ "firstName" : ["Homer", "Lisa", "Bart", "Marge", "Maggie"]

"age": [39, 8, 10, 36, 1]

}

But, what XML sacrifices in computational tractability and independence it makes up for in expressivity. Our schema, which is defined in the second line <simpsons:family xmlns:simpsons="http://training.mulesoft.com/simpsons""> uses a namespace http://training.mulesoft.com/simpsons to define a class of instances simpsons as well as properties of those instances, such as last-name, first-name, and age. This syntax gives us a semantic meaning - our computers don’t just think “this is a member of a list” but instead our computers know “this is an instance of the simpsons class that has the property ‘first-name’ and the value ‘Homer’”

To reiterate something you’re going to get sick of me saying: The tradeoffs in choosing between XML and JSON, or really any logical level data abstraction, are about balancing the need for tractability and expressivity. For textual data that contains many nuances implied in the semantic content, we want to choose something like XML. When we need to privilege fast computation (e.g. retrieval) and data independence then we are more likely to choose something like JSON. Neither approach is right or wrong, but each choice comes at a cost.

Triples

In thinking about differences between tables and trees - we recognize that each has certain affordances and limitations. In describing the affordances of a markup language for trees I stressed its “semantic” power by saying:

our computers don’t just think “this is a member of a list” but instead our computers know “this is a member of the simpsons, that has the property ‘first-name’ and the value ‘Homer’”

The fact that our computers are knowledgeable about the semantic meaning of data, through our notation system, means that we could, in theory, design a system that takes greater advantage of this semantic meaning. At the logical level, if we use a schema to define instances as members of classes, we could also assign properties to those instances. And, by relating those properties to one another, we could start to know something about how instances and class membership relate to each other.

In short, this is the ambition of the semantic web - by storing information about objects and instances at the logical level we can build powerful “inferencing systems” that can use logic to reason about the semantic content of our data based on their properties. Where this starts to take a “Eureka!” turn is that by defining a small set of formal logical relationships our computers can start to infer (without explicit direction) relationships that should exist between instances and classes based on their properties.

For example, if we know that Lisa is the daughter of Homer and we create a logical rule that all daughters identify as gender:female and that all daughter: age are necessarily less than father:age then we can reasonably infer some things about Lisa: We know that Lisa is a female and that, by being the daughter of Homer she is younger than he. And, we know this without having to explicitly state that Lisa is a female - our computers can simply reason this through the logical statement that “All daughters identify as female, and Lisa is a daughter.”

If we also know that Homer has a son Bart we can also infer some more information about both Lisa and Bart : We can infer that Lisa has a brother Bart and transitively Bart has a sister Lisa. We know all of this by defining the logical relationships between sons, daughters, gender identities, fathers, and siblings in our schema.

The natural language expressions that appear above have simple logical syntax that are the basis of a notation language known as “RDF” or the Resource Description Framework. In RDF, a triple is the formalization of a natural language statement that consist of three components: 1. Subject; 2. Object; and, 3. Predicate. An example of an RDF triple statement like “Lisa has a brother Bart” contains the subject:Lisa, the object:Bart, and the predicate:has_a_brother. In an RDF schema, we could define the logic of a predicate like has_a_brother such that “all brothers identify as male”, and “all brothers have a sibling”, and “all brothers and sisters share at least one parent”. This declaration in our scehma let’s our computers infer that a statement like “Lisa has a brother Bart” means, without explicitly stating it, that Bart identifies with the gender male, and that he shares at least one parent with Lisa.

RDF triples, by using logic to define relationships between instances and classes, become the most powerful of all three choices we have at the logical level of data representation. (Do you anticipate a “but . . .” coming?) But, creating a logically coherent RDF schema is an incredibly difficult task. Triples, and all of their inferential power, are both computationally expensive to retrieve, and descriptively difficult to create and maintain. The tradeoff that we face between tables, trees, and triples presents a modification to the one I’ve discussed thus far - between tractability and expressiveness. The new tradeoff we have is inference, or intelligence: If we want a logical level data representation that is “artificially intelligent” - that is it can infer without explicit directions - then we have to sacrifice some expressivity and a lot of tractability.

We will return to the concept of the Semantic Web and RDF in the 10th week of class, but its helpful to have this logical level data representation in mind as we work through the quarter. In part, because RDF and the Semantic Web are an emergent way of curating data to provide meaning for end users. At the same time, the Semantic Web has been “five years away” since 1998.

Summary

In this chapter I introduced a number of concepts. Here’s a brief review:

- Levels of abstraction. These include a separation between how we represent data in terms of concepts, logic, and physical storage (See Figure 1 for a quick overview).

- Data Independence is the ability to separate data encodings from the logical level where it is managed and made accessible to users. By making data independent from its storage we can easily modify, and add data at the logical level.

- Notation languages, such as XML, JSON, and RDF all have tradeoffs. In DC I we described these tradeoffs in terms of expressivity and tractability. In DC II we introduce the idea of “intelligence” to data representation, but we hold this at arms length because it comes at such a high curation cost.

Lecture

Readings

The following blog post is an easy to digest look at the different data shapes we’ve discussed in this module. If you’re already familiar with tables and nested lists you can skim this.

- Kodes, Katie (2019) Data’s Shape

Additional readings this week are from the W3C standard for Data on the Web. W3C is the World Wide Web Consortium - the main standardization organization for web technologies. In 2017 a working group of experts in data curation came together to develop a set of best practices for structuring, publishing, and making data on the web accessible. The Best Practices document is an excellent resource to return to as you develop your protocol and if (when) you find yourself working in a data curation role.

- Lóscio et al (2017) Data on the Web - Best Practices: https://www.w3.org/TR/dwbp/ (If you are pressed for time, you can probably skim the content through to section 8 where the specific best practices begin.)

- Read one additional Data on the Web - Use Case from this list: https://www.w3.org/TR/dwbp-ucr/

In future weeks we will use the Data on the Web primer for activities related to our data curation protocol.

Optional Readings

For a bit of historical background, Ch 1 of this book (pages 1-13) provides an excellent overview of how data were originally made compliant with web standards. The rest of the book also provides a great overview of data models and database integration more generally, but it is very much a lengthy and time intensive read:

- Abiteboul, S., Buneman, P., & Suciu, D. (2000). Data on the Web: from relations to semistructured data and XML. Morgan Kaufmann. PDF

Exercise

In preparation for our class on Tidy Data next week we will attempt to add some structure to a rather innocuous piece of information that is published to the web and that maybe you’ve encountered even more frequently during COVID-19 quarantine: Chocolate Chip Cookie Recipes.

Imagine that you are starting a data repository specifically for cookie recipes. You get to choose how best to set up your repository. You are at the stage where you want to decide how to represent the data included in a recipe. Your exercise for this week is to look at this chocolate chip cookie recipe (PDF version) and choose to represent it as a table, tree, or triple. Use what you’ve learned in this module and this blog post as a guide for tables and trees. If you choose to make triples, start by outlining the subject - object - predicate relationship. If you want to get fancy, take a look at this blog post.

Some things to keep in mind:

- Don’t worry about using established metadata schema for this exercise (we’ll get to that later). You can make-up the schema (i.e. the column names or tags used to indicate the variable, the namespaces) and you don’t need to create definitions for the metadata, just make sure your terms are fairly self-explanatory (e.g. use

ingredientinstead ofthing). - There isn’t a “right” answer to which representation you choose

- On the canvas forum, share your representation with the class, and explain why you made the choices you did. What was difficult, what was easy? You can share this in whatever form you like (create one directly in Canvas, link to a Google Doc, Upload an Excel file, post a .jpg of your hand-drawn representation, etc.)