Wrap Up

or “What I wish I had integrated into the curriculum prior to day 1”

Author: Bree Norlander

The main reading I wanted to find a place for (and ultimately never did - unless you count right now) this quarter is “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big? 🦜” (and not just because it includes an emoji in the title, though that in itself is certainly novel). If you have time this week, read it. If you don’t, read it later.

It is past time for researchers to prioritize energy efficiency and cost to reduce negative environmental impact and inequitable access to resources — both of which disproportionately affect people who are already in marginalized positions. (p. 613)

we discuss how large, uncurated, Internet-based datasets encode the dominant/hegemonic view, which further harms people at the margins, and recommend significant resource allocation towards dataset curation and documentation practices. (p. 613)

This fourteen-page article about one particular type of dataset encapsulates so many issues I want you to think about as you embark on data-related (or other) careers. (Additionally there are issues regarding the response by Google to Timnit Gebru’s and Margaret Mitchell’s roles in publishing this article, but I’ll just focus on the content of the paper for now.)

Let me set the stage. Stochastic Parrots is specifically about natural language modeling (used for auto-generating text, machine transcribing, automated speech recognition, and more) and the datasets used in the process:

One of the biggest trends in natural language processing (NLP) has been the increasing size of language models (LMs) as measured by the number of parameters and size of training data. (p. 610)

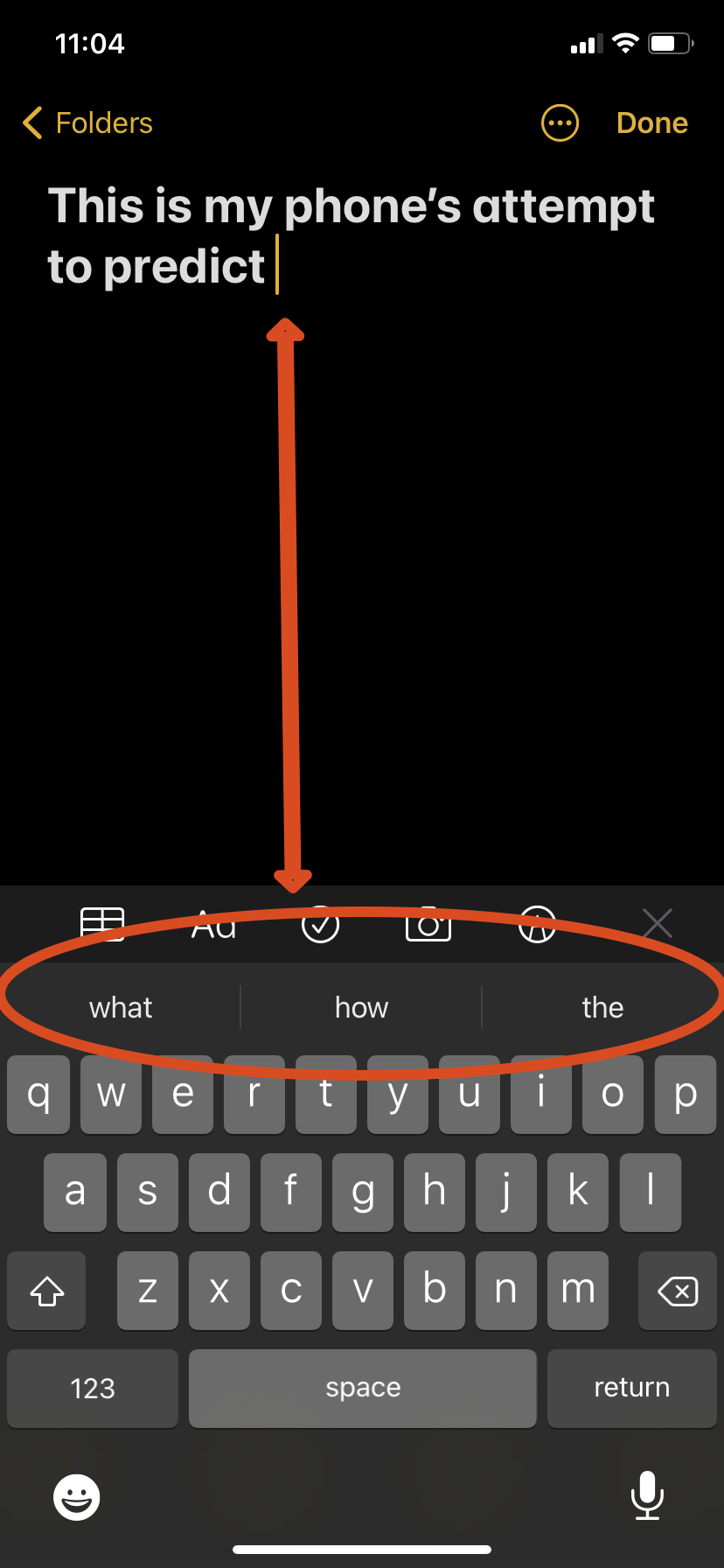

Here the authors are referring to two pieces of natural languague processing, models and datasets:

- Language models, which are calculations of probabilistic relationships between words (e.g. the likelihood that certain words will follow a given string of words), that are “trained” on

- datasets full of natural language examples. These datasets can come from anywhere in which there is spoken or written language to extract (books, emails, tweets, reddit posts, blogs, on and on).

And, size, which refers to the computational and storage size of language models. The datasets themselves are large, and then the probability modeling on top of the large datasets can be extremely resource intensive (in energy consumption, memory consumption, CPU workload, etc.).

As you work through this piece, you will likely come across technical terms that you are unfamiliar with and that likely have more to do with language models than with the datasets (though the authors really do an excellent job of defining almost everything which is such an asset to a technical paper). That’s OK. I want you to pay attention to the real-world environmental and ethical issues that arise when we think about natural language datasets and their use. That’s what we are doing as data curators, thinking through the preservation and re/use of the datasets we are making available.

In accepting large amounts of web text as ‘representative’ of ‘all’ of humanity we risk perpetuating dominant viewpoints, increasing power imbalances, and further reifying inequality. (p. 614)

OK, enough set-up…go read the article.

Now, what questions do you have about the role of data curation? Why is this article relevant? Here are some of the thoughts I walked away with:

- This article talks a lot about data curation and data documentation. How do the authors’ definition of those activities resonate or differ from the activities we’ve learned about this quarter?

- In my experience in LIS, we want to save/preserve everything. Not that long ago digital storage was cheap and plentiful and we set about to preserve every digital artifact. This is not sustainable. Can we start to incorporate the environmental impact of data preservation into protocols for preservation? What does that look like? How do we weigh the costs and benefits?

- As we work to dismantle systems of inequity and injustice, what is our role as data curators in vetting datasets for erasure, bias, marginalization, and harm?

I present this article and these questions to you without answers. More than anything, I want you to have these questions in mind as you go about your work. You may end up in a position to advocate for better use of environmental resources, better vetting of datasets, more pre-mortem discussions of the data gathering process, and I hope you do. We need you in the field.

In summary, we advocate for research that centers the people who stand to be adversely affected by the resulting technology, with a broad view on the possible ways that technology can affect people. This, in turn, means making time in the research process for considering environmental impacts, for doing careful data curation and documentation, for engaging with stakeholders early in the design process, for exploring multiple possible paths towards longterm goals, for keeping alert to dual-use scenarios, and finally for allocating research effort to harm mitigation in such cases. (p. 619)

Additional Reading on the Topic

In addition to the costs (environment, financial, opportunity) and harms discussed in Stochastic Parrots, other researchers are looking very closely at some of the datasets used to train these models and finding copyright violations, content duplication, and genre biases (see Jack Bandy’s post).

Brandon Locke and Nic Weber have a chapter currently in publication called “Ethics of Open Data”. Nic has generously allowed you pre-publication access to this chapter, but you will need Canvas access to download it. It is an excellent overview of open data through the lens of virtue, consequential, and non-consequential (deontological) ethics including three relevant case studies. Future iterations of this course will no doubt include this text throughout the modules.

Advocacy and Solidarity Through Data Curation

Original Author: Nic Weber

Editing & Updates by: Bree Norlander

These past 18 months have put a spotlight on so many injustices, inequities, and wrongs. It has been a period of exceptional upheaval at systems that are deeply broken. Throughout the course content we have tried to make the content relevant in the examples used, but we have certainly at times fallen far short of what should be a course that equips you with skills to advocate and work on behalf of just outcomes. This is a work in progress and we aim to continue revising and making content that promotes justice, equity, and advocacy in data curation.

If you continue on at the iSchool we strongly recommend courses taught by our brilliant colleagues Megan Finn, Miranda Belarde-Lewis, Clarita Lefthand Begay, Marika Cifor, Jason Yip, and Anna Lauren Hoffman. A few that we recommend in particular are:

- LIS 534 Indigenous Systems of Knowledge (Belarde-Lewis)

- LIS 553 Information and Social Justice

- LIS 577 Participatory Design in Libraries (Yip)

- LIS 583 Cross Cultural Approaches to Leadership (Belarde-Lewis)

- INFO 498 - Data Ethics (Hoffman)

- INFO 402 - Gender, Race, and IT (Cifor)

- INFO 350 - Information Ethics and Policy (Finn)

Data Feminism & Activism

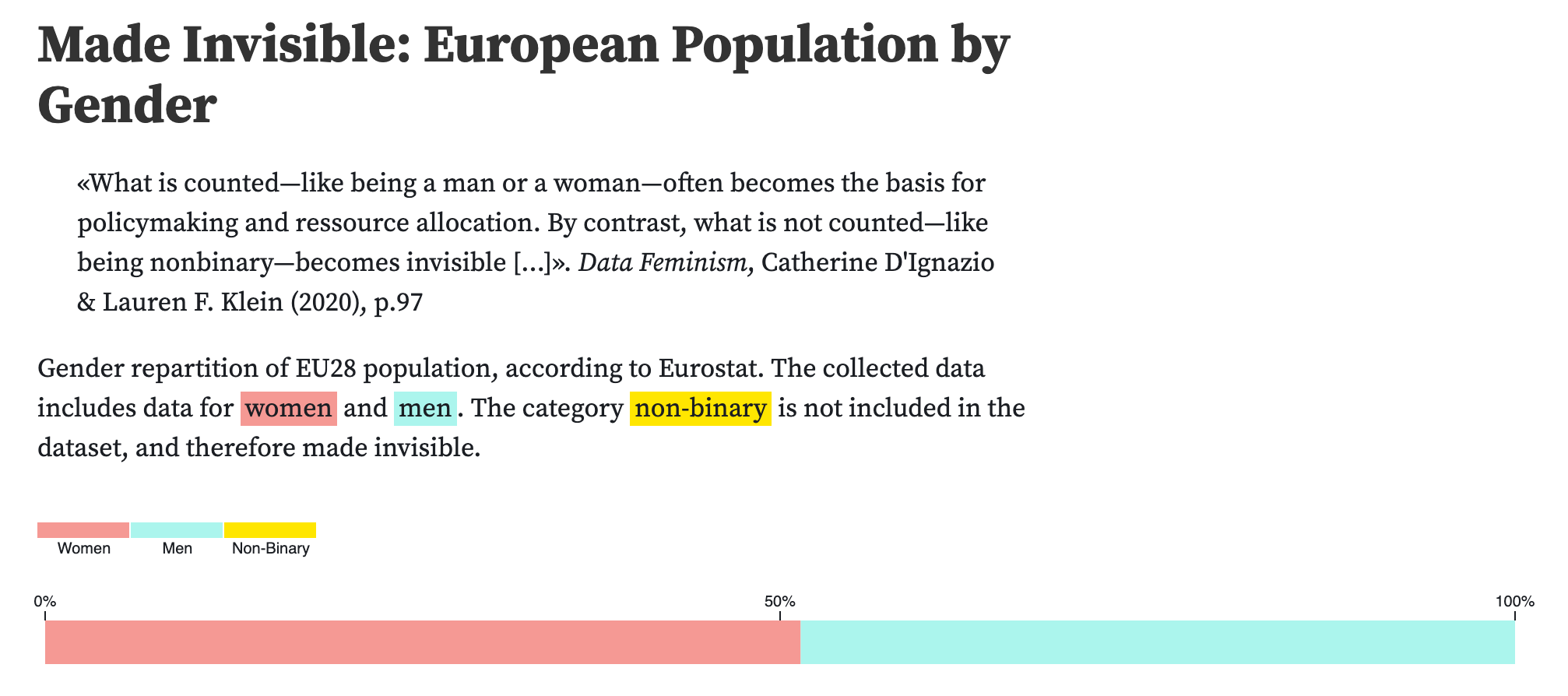

I can’t say this any better than the blurb for a book authored by Catherine D’Ignazio and Laren F Klein, “Today, data science is a form of power. It has been used to expose injustice, improve health outcomes, and topple governments. But it has also been used to discriminate, police, and surveil. This potential for good, on the one hand, and harm, on the other, makes it essential to ask: Data science by whom? Data science for whom? Data science with whose interests in mind? The narratives around big data and data science are overwhelmingly white, male, and techno-heroic. In Data Feminism, Catherine D’Ignazio and Lauren Klein present a new way of thinking about data science and data ethics—one that is informed by intersectional feminist thought.”

Through a critical lens that takes seriously the role of fourth wave feminism this book, and the advocacy around data feminism, should be a central place to locate the role of curation in contemporary society. The ability to structure, organize, and encode data cannot (as we have discussed throughout the quarter) be divorced from broader societal and institutional forms of power. By approaching these topics of curatorial power rooted in a historical understanding of oppression and civil liberties we might be able to, regardless of our identity and positionally, be more effective allies. I don’t presume to know how, given varied contexts, to do this most effectively, yet. But the emergent scholarship around data feminism is an excellent place to begin.

Here are some relevant resources to get started (or continue):

- The authors have made the entire book available open access here: http://datafeminism.io/.

- A brief blogpost and a podcast with the authors can be found here: https://datasociety.net/library/data-feminism/.

- I (Bree) watched an fantastic panel presentation with D’Ignazio through the Sasaki Foundation on March 25, 2021 and I keep checking to see if they’ve put the recording up, but they also have some great resources to go with the presentation here: https://www.sasakifoundation.org/events/.

- Here’s another podcast which goes into greater theoretical depth with the authors.

- Feminist Data Manifest-No (Organized and led by iSchool professor Marika Cifor): https://www.manifestno.com/

- Another execellent and relevant book is Christina Dunbar-Hester’s Hacking Diversity: The Politics of Inclusion in Open Technology Cultures

Data For Black Lives

Straightforwardly - many of the systems of observation and enumeration in state-based data collection are deeply biased against people of color. From the use of flawed algorithmic systems in unemployment benefits to the facial recognition technologies that are employed with deep biases related to black faces.

Perpetuating discriminatory policies through technologies that collect and are trained on imperfect data about people of color is a multi-faceted problem. Overcoming and effectively dismantling these flawed technologies requires effective policy development, legal expertise, and ethically trained data professionals. There is no simple way in which we can educate, legislate, or adjudicate our way out of the biases of technologies that are being increasingly used for harm. As data curators our role is first to become informed about the ways in which both technologies for data collection, and resulting data do harm. Second, we can begin to intervene where our skills and our expertise are appropriate. This will likely include volunteering our time to investigate and describe problems related to data encodings, efficient data processing, and documentation which surfaces bias and attempts to clarify why data are never neutral.

Here are some relevant resources to get started (or continue):

- Data 4 Black Lives

- Covid tracking by Race: https://covidtracking.com/race/dashboard

- Covid Black: Data and stories about Black health.

- Black Software: The Internet & Racial Justice, from the AfroNet to Black Lives Matter (not expressly about data, but a beautiful overview of the history of technology in the context of a connected web of information communication technologies) Book + Podcast

- Algorithmic Advocacy Toolkit Website

- An excellent example of data advocacy is the Mapping Police Violence project. You can see their data documentation here: https://mappingpoliceviolence.org/aboutthedata

Emerging Topics in Data Curation

Author: Nic Weber

Data Curation Future Directions

This final module discusses the future in data curation. Data curation is a fast moving field that responds to emerging needs of data producers, consumers, and users. Many emerging topics in data curation are beyond the scope of a 10 week quarter, but are worthy of our time and attention. Below, I cover some interesting topics and provide resources that you can use for future reference.

These are also not just my thoughts - I asked friends and collaborators to tell me what emergent topics they thought were most important for the future of data curation. Below are their responses (and my own thoughts).

Ontologies for Linked Data

In our previous chapter on linked data I described a rapidly evolving “cloud” or graph of linked data published to the web. Linked data are often governed by formal ontologies or vocabularies that include class, sub-class, properties and instances of data. These formalisms allow for data to follow a common markup (a standard), and these standards in turn enable relationships between data to be formally expressed and acted upon by machines.

The difference between a “vocabulary” and an “ontology” is often, ironically, semantic - ontologies are really just formal vocabularies that give linked data practitioners standard terms to define subjects, objects, and predicates for markup of data. As the W3C notes:

There is no clear division between what is referred to as “vocabularies” and “ontologies”. The trend is to use the word “ontology” for more complex, and possibly quite formal collection of terms, whereas “vocabulary” is used when such strict formalism is not necessarily used or only in a very loose sense. Vocabularies are the basic building blocks for inference techniques on the Semantic Web.

Even though I argued in our previous module that the semantic web has failed in many respects - where this field has succeeded is in providing useful ontologies for common data on the web. In the example I used for Austin, TX, the ontology that powered our linked data was DbPedia. By providing for standard ways to mark-up the subject, object, and predicates for Austin, TX, we were able to use simple declarations to query DbPedia to find the population of Austin, TX without having to explicitly state this factual information. In practice, this markup looked like the following:

<http://dbpedia.org/resource/Austin,_Texas>

<http://xmlns.com/foaf/0.1/based_near>

<http://sws.geonames.org/4671654/austin.html>

In terms of linked data - what we used were namespaces from the ontology that were defined on the web. If you click on the first namespace - you see all of what DbPedia knows about Austin, TX.

This allows for a plain language statement like “Austin has a population of 964,254” to take on a machine-readable statement like the following:

- Subject http://dbpedia.org/resource/Austin,_Texas

- Predicate: dbo:PopulatedPlace/populationDensity

- Object: 964,254

The key here is that DbPedia provided the subject and predicate statements - that is we used a resource in DbPedia to describe a particular place (Austin, TX) and we used a predicate from the ontology dbo:PopulatedPlace/populationDensity to connect the Subject to an Object (the actual population of Austin, TX). Our machines can interpret and know this semantic information simply through syntax. The ontology does all of the work in defining what a resource is, what a predicate means, and what the resulting object value is.

Ontologies are rigid in that they require very specific syntax, but they are also incredibly powerful in that they provide for so much of the standardized factual information we expect (and know) to already exist on the web. DbPedia is just one node in the emerging linked data graph. By understanding and using ontologies of linked data, as we discussed last week, we can connect our data (however locally specific it may be) to this web of information. The key to really understanding and using ontologies effectively is to know which ones exist, and to master their syntax.

Here are some resources to continue exploring linked data and ontologies:

- W3C description of ontologies

- Bennett, M., & Baclawski, K. (2017). The role of ontologies in linked data, big data and semantic web applications. Applied Ontology, 12(3-4), 189-194. This provides a critical but helpful overview of the role of ontologies in linked data. PDF

- Munir, K., & Anjum, M. S. (2018). The use of ontologies for effective knowledge modelling and information retrieval. Applied Computing and Informatics, 14(2), 116-126. PDF

- A handy Linked Data Glossary

- A very accessible and searchable list of Linked Data Ontologies

Sensitive Data & Privacy

The curation of data containing sensitive contents, including personally identifiable information (PII), is an emerging challenge for curators. As more personal data is collected there are increasingly valuable applications for responsibly using PII to generate valuable knowledge. Here are two emergent examples that are worthy of our attention:

- Contact tracing: You have likely been hearing about or reading proposals for automated contact tracing in response to the Covid-19 viral outbreak. At the heart of these discussions is how to reliably store, and provide access to personally identifiable information so that public health officials can reliably intervene in cases where an infected person is identified. The tradeoff between identification and anonymity is a difficult one to balance. It requires that we design decentralized data storage architectures that can reliably encrypt PII, and trust that only those with proper credentials have access to resolve queries against these data stores. Decentralization is an incredibly complex problem in all web-based technolgoies that depend upon personal data and will be a topic that continues to play an important role in future curation work.

-

- This is a very good recent paper on the topic: Li, T., Faklaris, C., King, J., Agarwal, Y., Dabbish, L., & Hong, J. I. (2020). Decentralized is not risk-free: Understanding public perceptions of privacy-utility trade-offs in COVID-19 contact-tracing apps. arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.11957. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2005.11957.pdf

- Census Data: The 2020 census will be the latest in what are regular full surveys of the United States population. The census is key for accurate counts of people, their mobility, and for policymaking. The census is also a key source of demographic data about the USA- used broadly in social science, epidemiology, and legal scholarship. As such, access to reliable administrative micro-data (for example, responses household level census surveys) is critical for research and development. In the past, a network of census data centers was set up to provide access to the most restricted of these data sources. The 2020 census data will be the first to release sensitive data using a process of differential privacy - an encryption algorithm that obscures personally identifiable information but provides statistically sound micro-data to researchers. The 2020 census is also the largest and most sophisticated use of differential privacy to date. This will provide an incredible use case for how data curators might design, and effectively govern the release of sensitive data, and will likely result in many accessible tools and services for 2020 census data.

If you read just one thing about the census and differential privacy I highly encourage the following primer:

- Nissim, K., Steinke, T., Wood, A., Altman, M., Bembenek, A., Bun, M., … & Vadhan, S. (2017, June). Differential privacy: A primer for a non-technical audience. In Privacy Law Scholars Conf. https://privacytools.seas.harvard.edu/files/privacytools/files/pedagogical-document-dp_0.pdf

Emulation

Throughout the quarter we have discussed the transformation of data from closed or proprietary formats to open formats (or plain text encodings) which enable data to be reliably reused across different computing environments. There are typically two ways to achieve these transformations: Migration and Emulation.

Migration is, quite simply, the reformatting of data - which depends upon moving content encoded in one standard to another (e.g. Excel to CSV).

In digital preservation an alternative approach to format migration is the practice of emulation. Emulation is, broadly, the reproduction of a computing environment in which a data format is rendered. This allows software or a program to be used in any hardware or computing environment.

Most of us have experienced emulation in the context of legacy video games. For example, when we play a version of “Super Mario Bros” in a browser this is the emulation of the original Nintendo console. This allows us to port the functions of Nintendo to our contemporary computing hardware. We no longer need an actual Nintendo console to play the games that were originally developed for that hardware.

Similarly, emulation is being developed for interacting with and using software that is necessary for reproducing analyses, interacting with research artifacts (e.g. simulations or dynamic graphs), and rendering data. Emulation was once exceptionally difficult and prohibitively expensive to develop, but is being made easier by what are called “containers” or “virtual machines” that allow for anyone to reproduce a computing environment in which data were analyzed and used.

Examples and further reading on Emulation:

- Yale’s Emulation as a Service https://web.library.yale.edu/emulation

- Code Ocean and the ability to “push a button” and rerun someone’s analysis is a good example of emulation as a service for research data. This is a good webinar video on the topic.

- Adam McMaster has a nice general blog post on using containers for research.